Dilli Chalo — Farmer Protests in India

Dilli Chalo — Farmer Protests in India

There was an incident not long ago where a convoy of small trucks rammed into a group of protesting farmers in India. It was a brutal attack, not that dissimilar to the one that happened in Charlottesville in 2017.

What led to such hate? I had seen many reports of farmer protests in the past, but honestly had never really took notice.

I wanted to change that, understand why Indian farmers have been protesting for more than a year now and how other social groups reacted to that.

For this, I was going to take advantage of the information being surfaced through discursus core, our open source data platform that mines, shapes and exposes the digital artifacts of protests, their discourses and the actors that influence social reforms.

And to make sense of that data, I want to introduce a first version of the framework we’ll use to analyse protest movements, as well as to guide the future developments of the discursus platform.

Why Are Indian Farmers Protesting?

Before we get into the results of our analysis, let’s give some background information into why farmers have been protesting for so long in India.

To get us started, I would recommend you take a few minutes to watch this short video by The Guardian on what those protests are about.

<a href="https://medium.com/media/44fe424a694b2eb37b4f8f047f17954d/href">https://medium.com/media/44fe424a694b2eb37b4f8f047f17954d/href</a>

This video does give prominence to the farmer’s point of view. And that’s where things get messy when trying to understand the dynamics of a protest. It’s that there are more than one actor involved in it. They have their own narratives and they also take part in the protests in their own way (even if some of their actions might be somewhat passive).

Each actor’s narratives and actions are preemptive or in reaction to another actor’s narratives and actions. So to understand the position of one actor, you need to understand how another actor positions itself.

In this case, we have to go back to India’s Green Revolution.

The Green Revolution

The Green Revolution was a period when agriculture in India was converted into an industrial system due to the adoption of modern methods and technology, such as the use of high yielding variety (HYV) seeds, tractors, irrigation facilities, pesticides, and fertilizers. — wikipedia

India’s agriculture is highly fragmented amongst farmers owning small parcels of land. This Green Revolution brought in modern agriculture techniques and prosperity, but also exposed farmers to liberal market dynamics.

Those dynamics caused financial stress on farmers. Most notably were the costs associated with production (for example Monsanto BT cotton seeds and associated pesticides and irrigation system) of the crops. Being small independent farmers, they are buying materials at retail price, as they do not have bargaining power.

The Green Revolution might have brought in increased productivity of crops, but farmers could only sometimes generate small profits and most of the time accumulate important debts. The farmer’s financial issues has led to an alarming rise of suicide rates.

Mandis

Since India’s independence, each government’s priority has been to control the price of food for consumers. To do that, a system has been put in place that essentially introduces a government-controlled middle-man between farmers and consumers. They are called Agriculture Produce Marketing Committees (APMCs) or Mandis.

Mandis are local markets where licensed traders buy farmer’s products at an agreed price (or at a minimum price, MSP, set out by government — more on that later). APMCs are the only ones who can buy from farmers. As there is no competition between Mandis, farmers are then protected from fluctuations of the market. Prices are set based on bargaining between farmers and traders, or based on that MSP set out by the government.

Farmer’s Bill

Just like the Green Revolution modernised / liberalised the production of crops, the Modi’s government has set out to modernise / liberalise the selling of agricultural products. The argument is that by exposing the marketing of products to a more open market, farmers should profit from it.

More than that, there are also pressures from the international community to remove subsidising of agriculture (although all countries do it to some extent). Also, the Mandis system is far from perfect, as traders tend to organise to “fix” the prices, which arranges them and not necessarily the farmers.

For all those reasons, the Modi government introduced the Farmer’s Bills, which consists of 3 laws that essentially aims to liberalise the selling of agricultural products by:

Removing the constraint for farmers to only sell to Mandis.

Removing the constraint of only selling locally.

Removing stocking restrictions

Surrounding those reforms, another important component that might get impacted are the Minimum Support Prices (MSP) that are set for certain crops. They essentially establish a floor price at which certain crops can be bought for, securing farmers against selling certain crops at a loss.

Reaction

Farmers weren’t as confident as the government that those reforms would be financially beneficial to them. It might make the agricultural sector as a whole more profitable, but it won’t necessarily be the small farmers that will reap the benefits.

Although there are quite a few contentious points for farmers, we could sum up their opposition to the farmer’s bills with those 2 arguments:

Complete liberalisation will consolidate the market towards major agri-corporations.

If trade happens outside Mandis, governments will eventually remove the Minimum Support Price on certain crops.

This has triggered a massive movement from farmers to protest the enactment of those reforms and led to blockades.

Analysing The Movement With Open Source Data

Observations from the discursus data platform

As we now understand the context for those protests, let’s see how this movement formed and gained momentum.

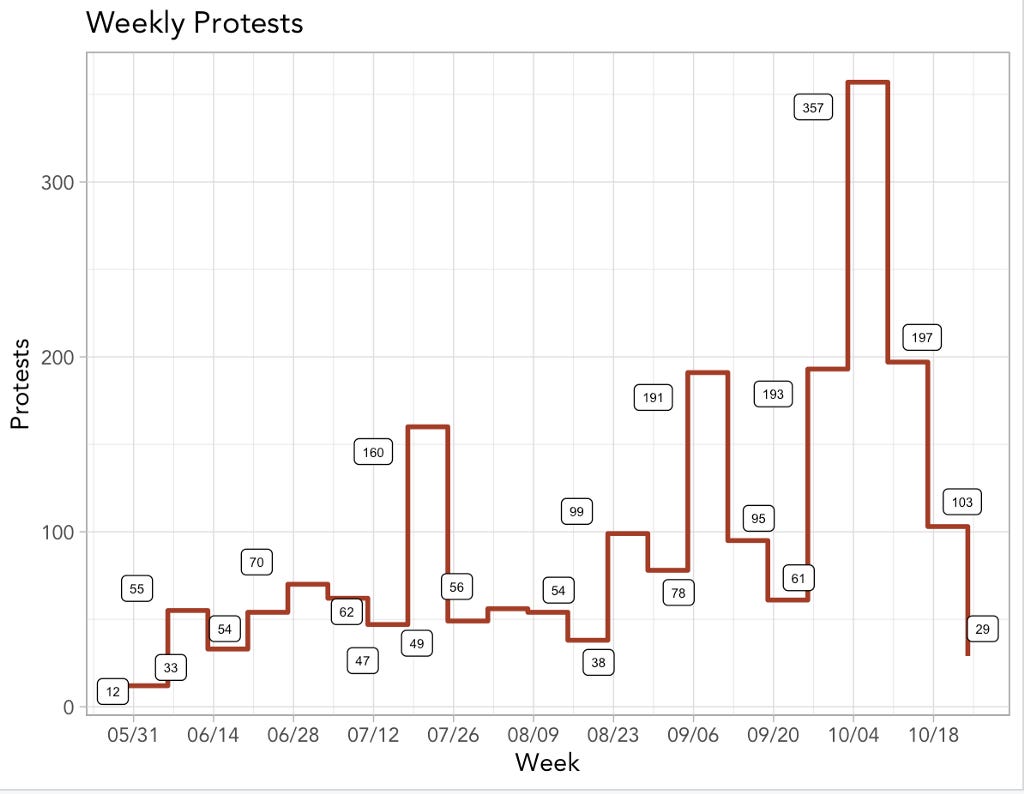

From our discursus data platform, we can see from the weekly protests how active the movement has been since June 2021 (date since we’ve started collecting data).

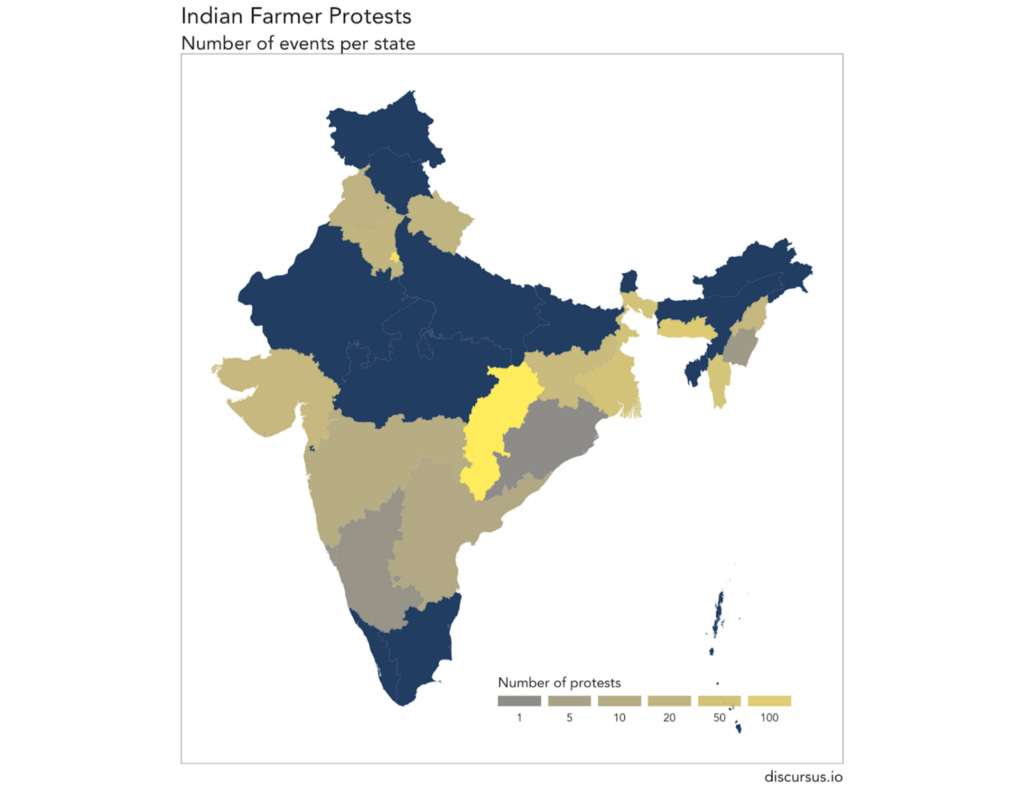

And when we break down the data by state, we can see how active the movement was in the southern part of India and how those farmers converged to Delhi to protest.

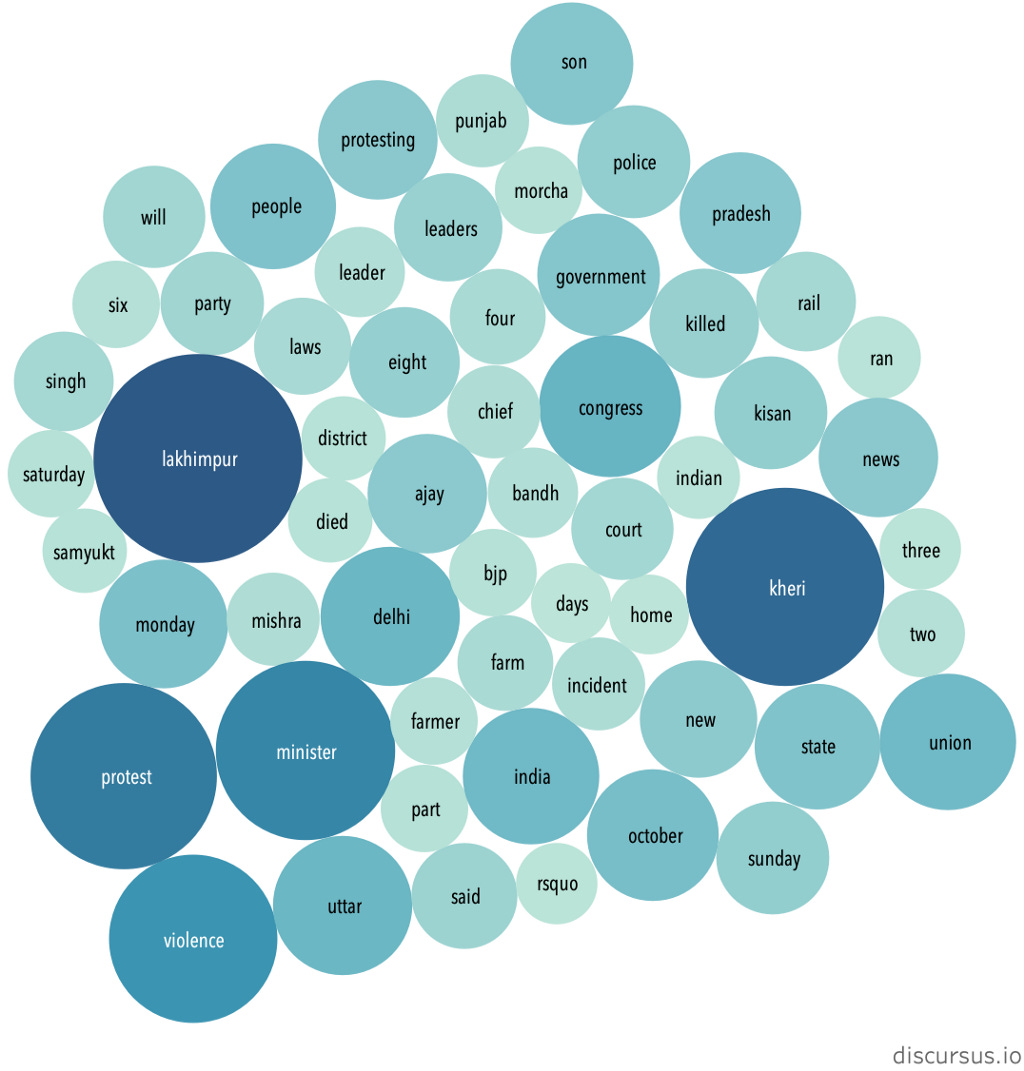

Finally, from all the related articles that were mined with the discursus platform, here’s a word cloud of the most relevant words that has described the farmer’s protests.

Introducing the discursus’ framework for protest analysis

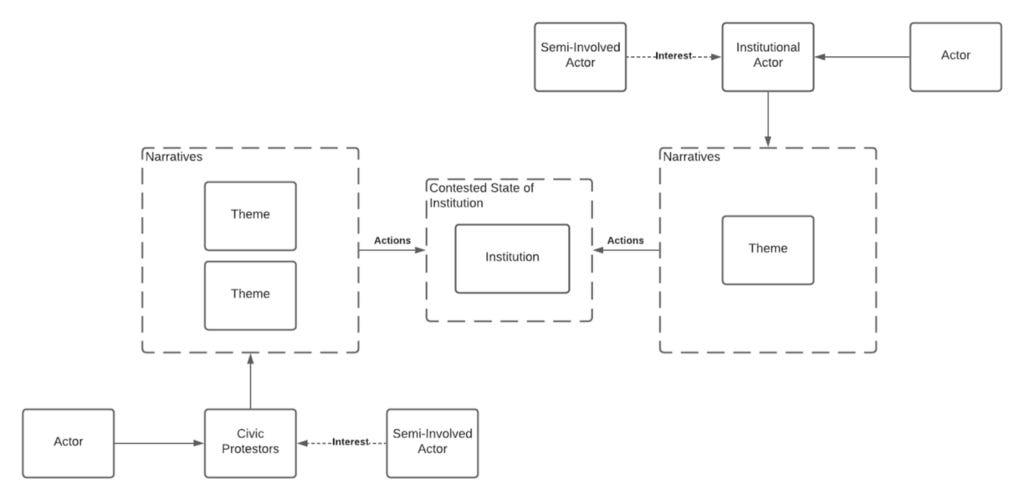

Now that we have context and data, let’s start introducing a framework of analysis that will conceptualise the main entities and how they interact within a protest movement.

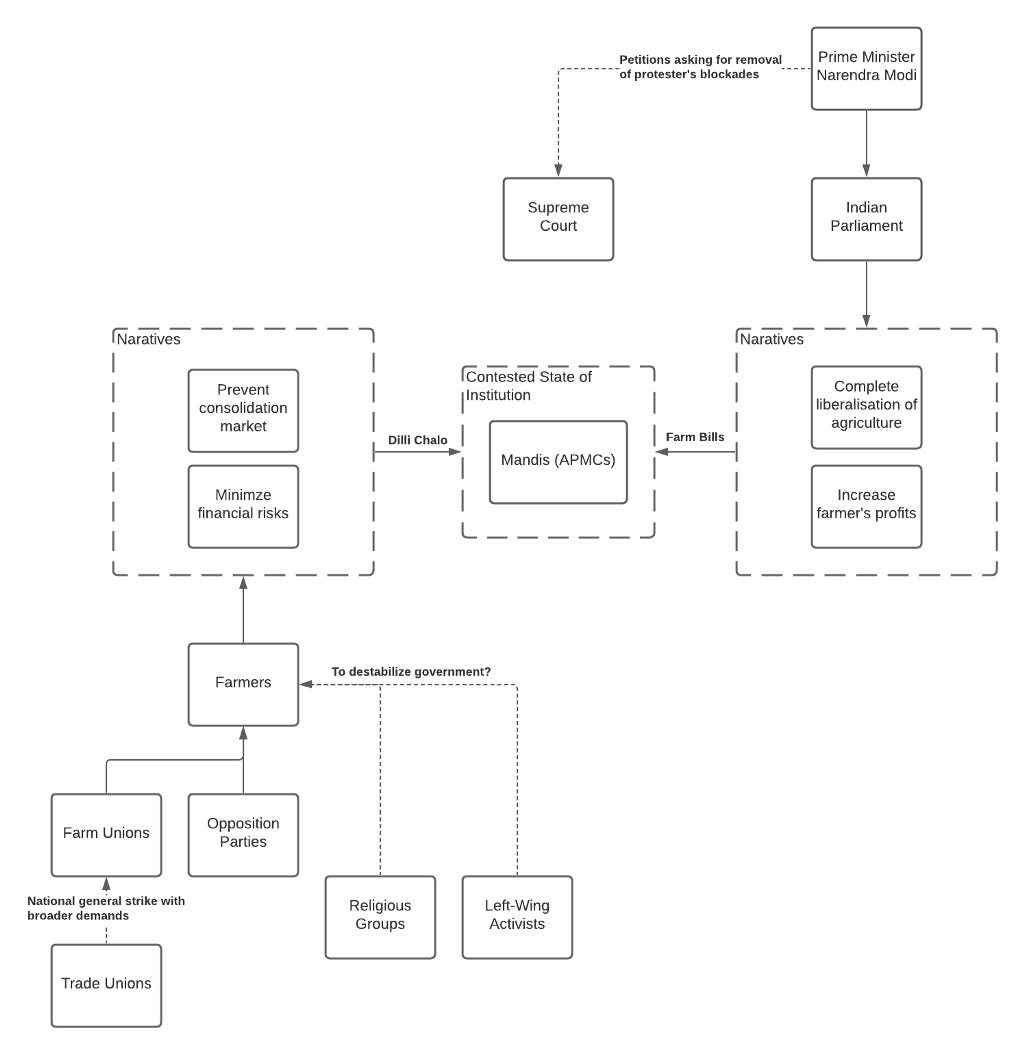

This first component of our framework maps the dynamic of a protest and has the following attributes:

Main focus is to map the dynamics between actors.

At the heart of that dynamic is an institutional status that is being promoted by one actor and contested by another.

Those points of views are framed within narratives.

Those narratives support actions from each party to alter / maintain the status of the institution.

Outside of that framework is public sympathy, which has an important influence on the outcome of such dynamics

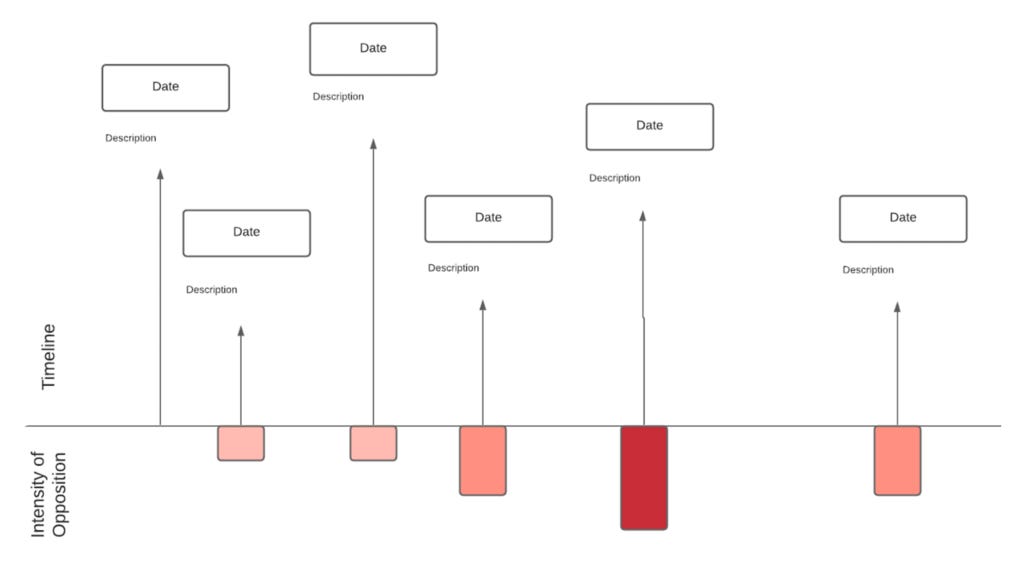

A second component of our framework is how that dynamic evolves through time.

This timeline has the following attributes:

A protest’s dynamic evolves through time.

Demands are received by institutional actors on a “listening spectrum”, which indicates the intensity of the opposition.

Depending on how well received the demands are, the protest actions get modulated in their intensity.

A protest thus goes through moments of tensions, rapprochement, rupture and reconciliation.

Actors morph as well, to acquire/lose groups, influencers, financial support, etc.

Applying the framework to farmer’s protests

Back to India’s farmer protests, here is how we’ve mapped its dynamic.

Let’s highlight some of the key attributes of this protest’s dynamic:

The main actors in opposition are the farmers and the Indian parliament.

Behind those main actors are supporting ones that are promoting their own interests. For example, PM Modi is probably politically motivated to pass those bills as a milestone in his own legacy. Farm Unions probably want to keep the status quo to preserve their influence in the current system.

At the heart of this dynamic is a suite of reforms that can be boiled down to changing the current Mandis system. The governmental actors want to dismantle that institution to liberalise the agricultural market, whereas farmers want to keep the system as is to prevent a consolidation of the market, as well as minimize financial risks.

The government introduced the Farm Bills to enact those reforms. Farmers started protesting locally, culminating in the Dilli Chalo movement which essentially means “Let’s go to Delhi”.

The timeline of this protest, as of October 26, 2021 is as follows.

The main highlights of how that protest evolved are:

After the introduction of the Farm Bills, there were rounds of talks between the government and the farmers which started to organise. This might have been a strategy to kill the protests by forming committees that delay decision making in the hope that agitation dies down. But in fact, the protests slowly started gaining momentum.

The Dilli Chalo rally culminated with the Republic Day protest which ended up with an open confrontation between government law enforcement officers and the mass of farmers that took Delhi by storm.

On October 3 2021, as mentioned in our introduction, a convoy of trucks rammed down a group of protesters, which has somewhat re-energised a movement that had been losing a bit of momentum since Republic Day protests.

As we mentioned previously, the invisible actor of our framework, public sympathy, is present throughout that timeline. Population seems to generally be supportive of farmer’s protests. They are the ones that put food on their table.

That said, there seems to also be an impression that governments are pampering farmers through their Minimal Support Price.

It is like gov is handing money directly in pocket of rich landowners or ‘farmers’ so they can sell their low cost products at a very high cost to the gov — quote pulled from a Discord chat group

Also, there was some criticism of the movement during Republic Day’s protest, when a minority associated to religious and left-wing groups deviated from others to take over the Red Fort.

Conclusion

In this article, we wanted to introduce a framework to analyse protest movements. The use of that framework in conjunction with the data collected by the discursus platform provides a richness of material and the means to better understand the dynamics of a protest movement and how it evolves.

Follow this publication for updates on the evolution of the open source discursus data platform, as well as new analysis of protest movements.